Key Milestones in the History of Cathay Cinema

The closing of Cathay cinema at Handy Road, one of Singapore’s oldest cinemas, marks the end of an era. Here’s a look at the Cathay Building and cinema over the years.

By Soh Gek Han

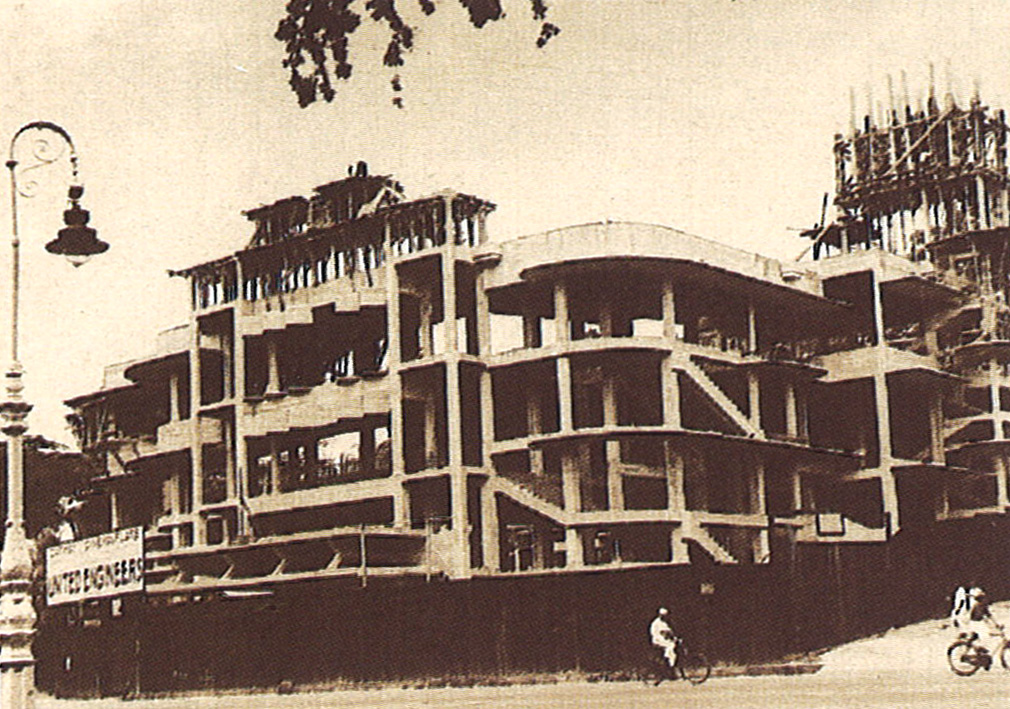

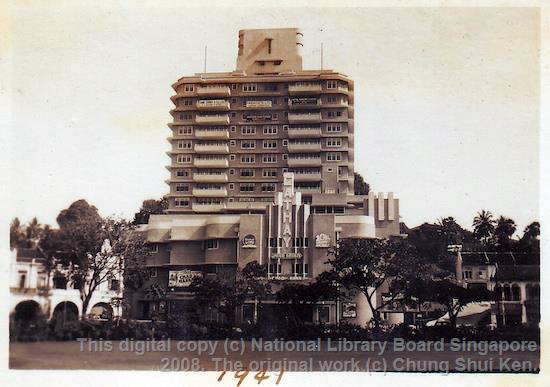

The First Skyscraper in Singapore

The 16-storey Cathay Building at the foot of Mount Sophia was once the tallest building in Singapore, at about 87 m (from the street level to the top).1 The front block of the building housed the Cathay cinema and Cathay Restaurant, and at the rear was the apartment block, which later became Cathay Hotel.

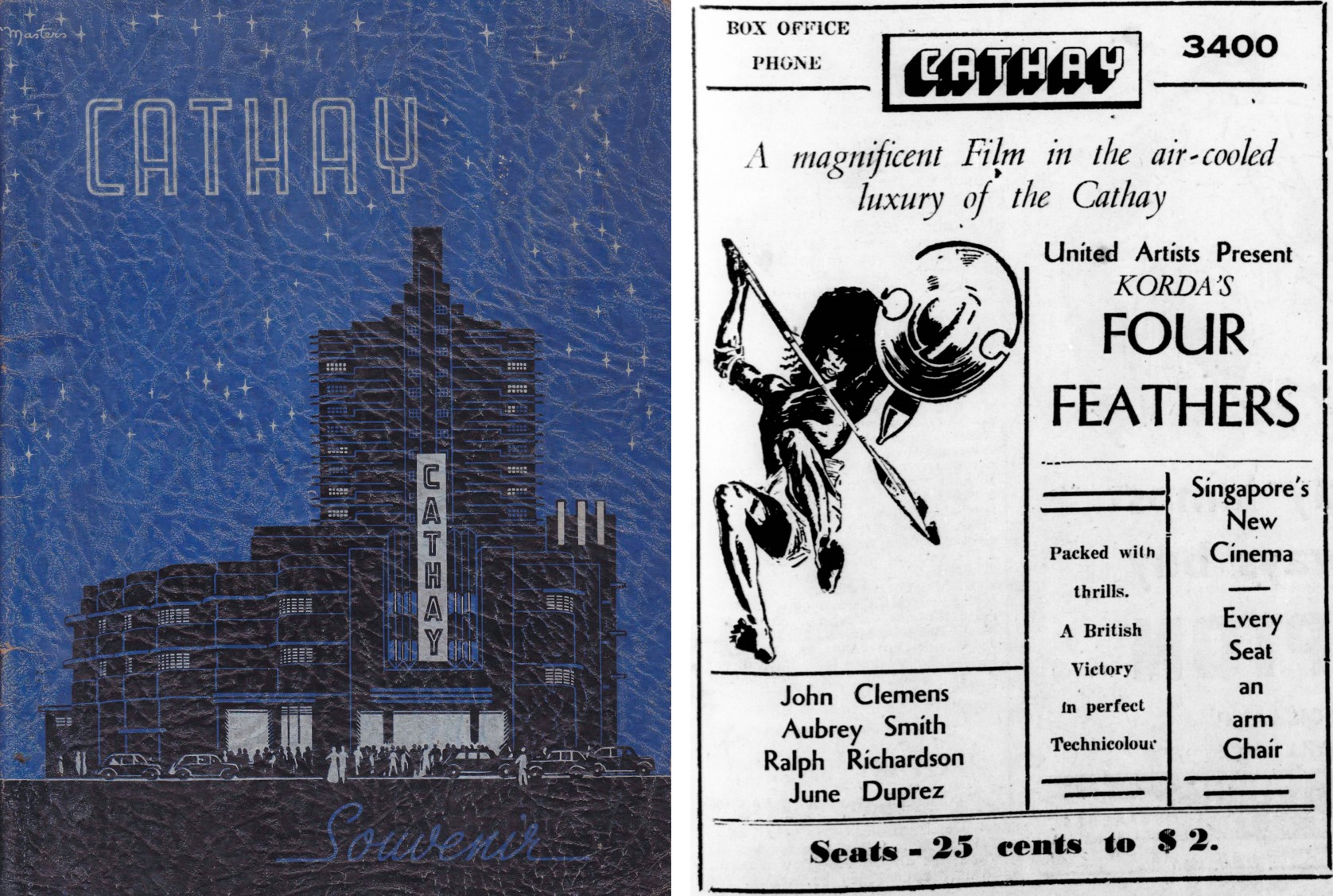

Grand Opening in 1939

The 1,321-seat cinema opened on 3 October 1939 with Four Feathers, a British adventure movie about the war in Sudan that was previously banned in Singapore on racial grounds.2

The theatre was opulent, with black marble pillars, green-tiled floors, silver curtains and gold ceilings. On either side of the screen was acoustic plaster in the shape of shells. 3

The Cathay Restaurant subsequently opened in 1940, and the apartment block in 1941. 4

World War II

In 1941, Cathay Building was leased to the colonial government and the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation. The latter continued to broadcast updates of the war during the Japanese invasion, and the cinema was used as a shelter in the last days before the Japanese Occupation.5

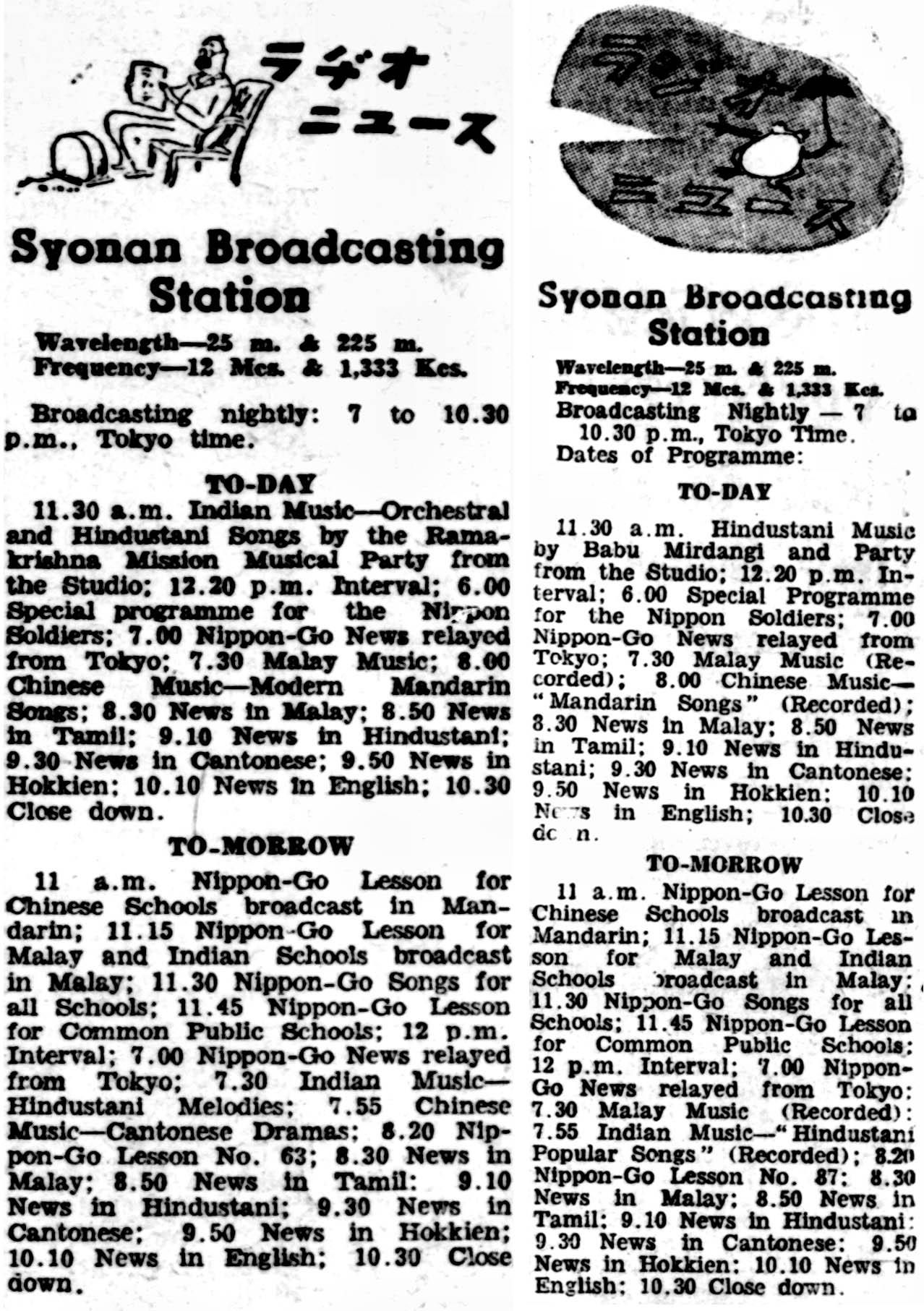

After Singapore fell to the Japanese, the building was renamed Dai Toa Gekijo (Greater Eastern Asian Theatre) and became home to the Japanese broadcasting department, military propaganda department and the military information bureau. Transmissions of Radio Syonan from Cathay Building began in March 1942.6

The daytime radio programme usually had Japanese lessons and songs for students, while the evening programme included a segment for Japanese soldiers, as well as news and entertainment in Japanese, Hindustani, Tamil, Malay, Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien and English.7

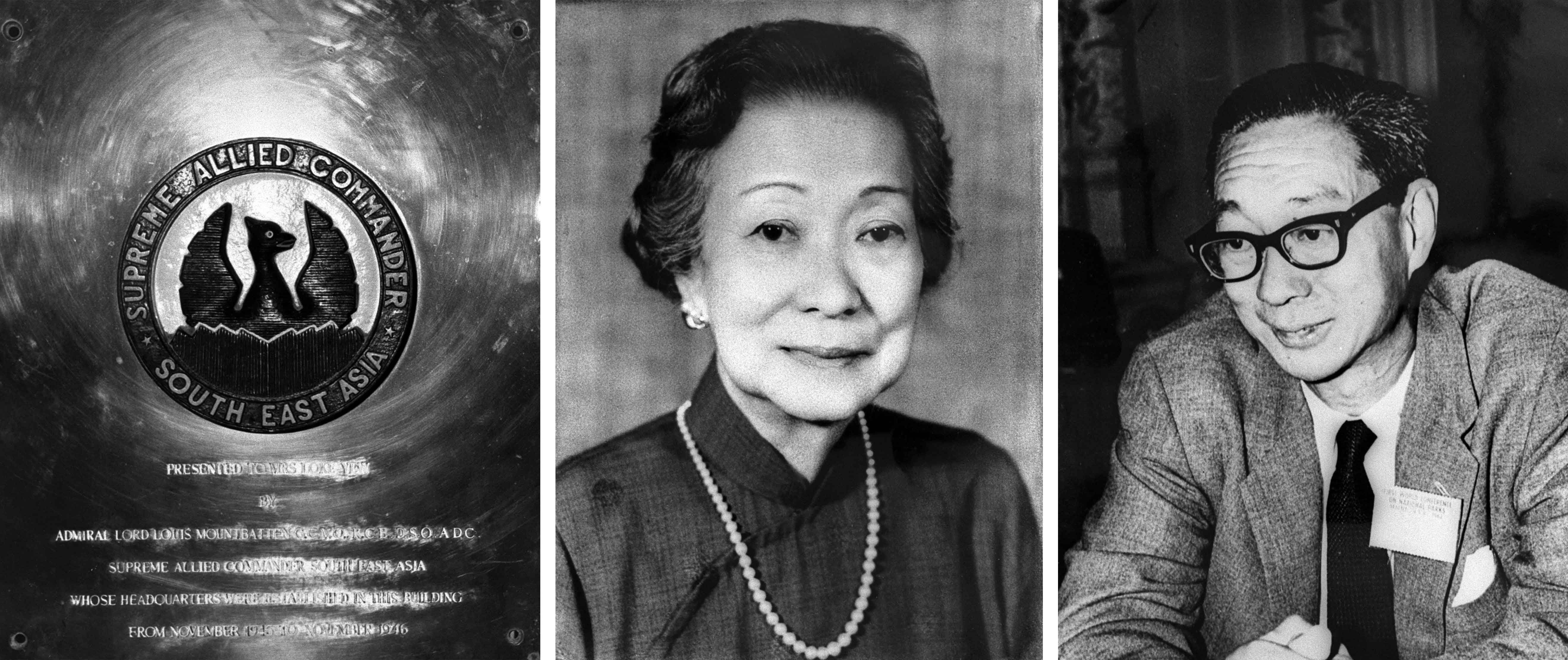

Headquarters for SACSEA

After the war, Cathay Building became the headquarters for Admiral Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander of Southeast Asia (SACSEA), from November 1945 to November 1946. To commemorate the setting up of the SACSEA headquarters, Mountbatten presented a brass plaque to Mrs Loke Yew and Mr Loke Wan Tho, owners of Cathay Building.8

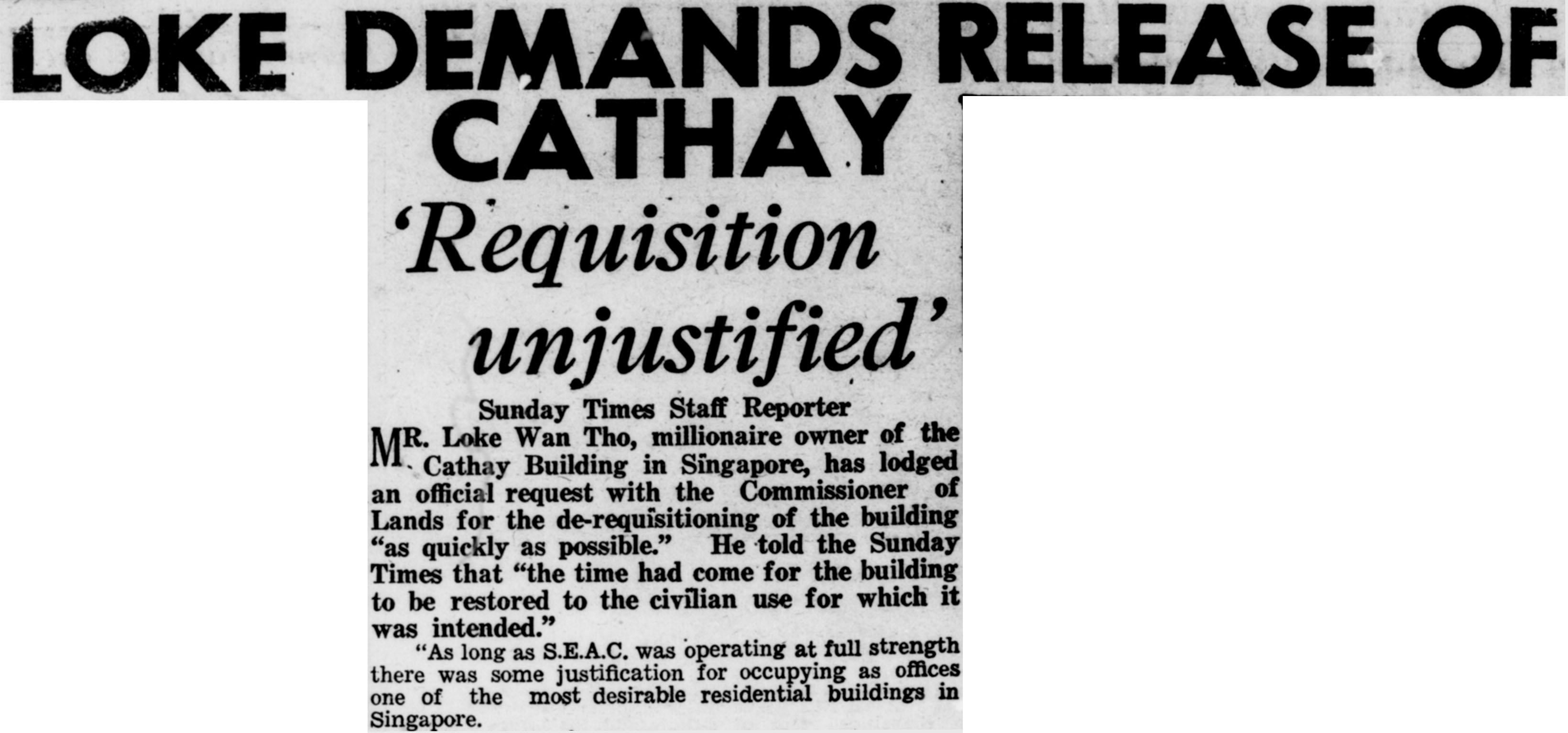

Cathay Organisation Regains Control

The cinema and restaurant reopened in September 1945 and May 1948 respectively, but it was only in February 1949 that the government vacated the building and Cathay Organisation regained full control.9 Cathay Hotel began operations on 9 January 1954.10

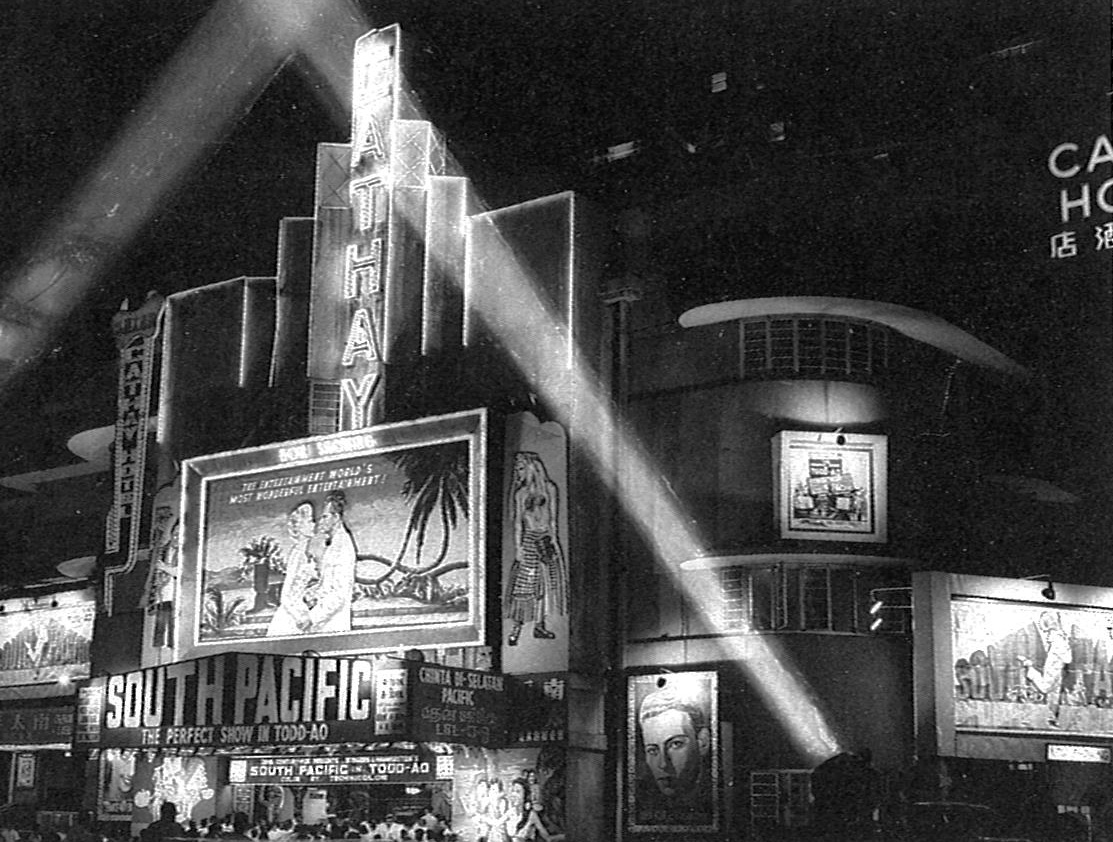

By 1955, Cathay Building was no longer the tallest in the land, but it remained a landmark in the city centre.11

Redevelopment

From the 1960s to 1990s, the building underwent various redevelopments. The hotel space was turned into office premises, and the hotel closed on 30 December 1970. The cinema was expanded from a single-screen to a multiplex in 1991.12

In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the end of WWII in 1995, the National Heritage Board erected a WWII plaque outside the building.13

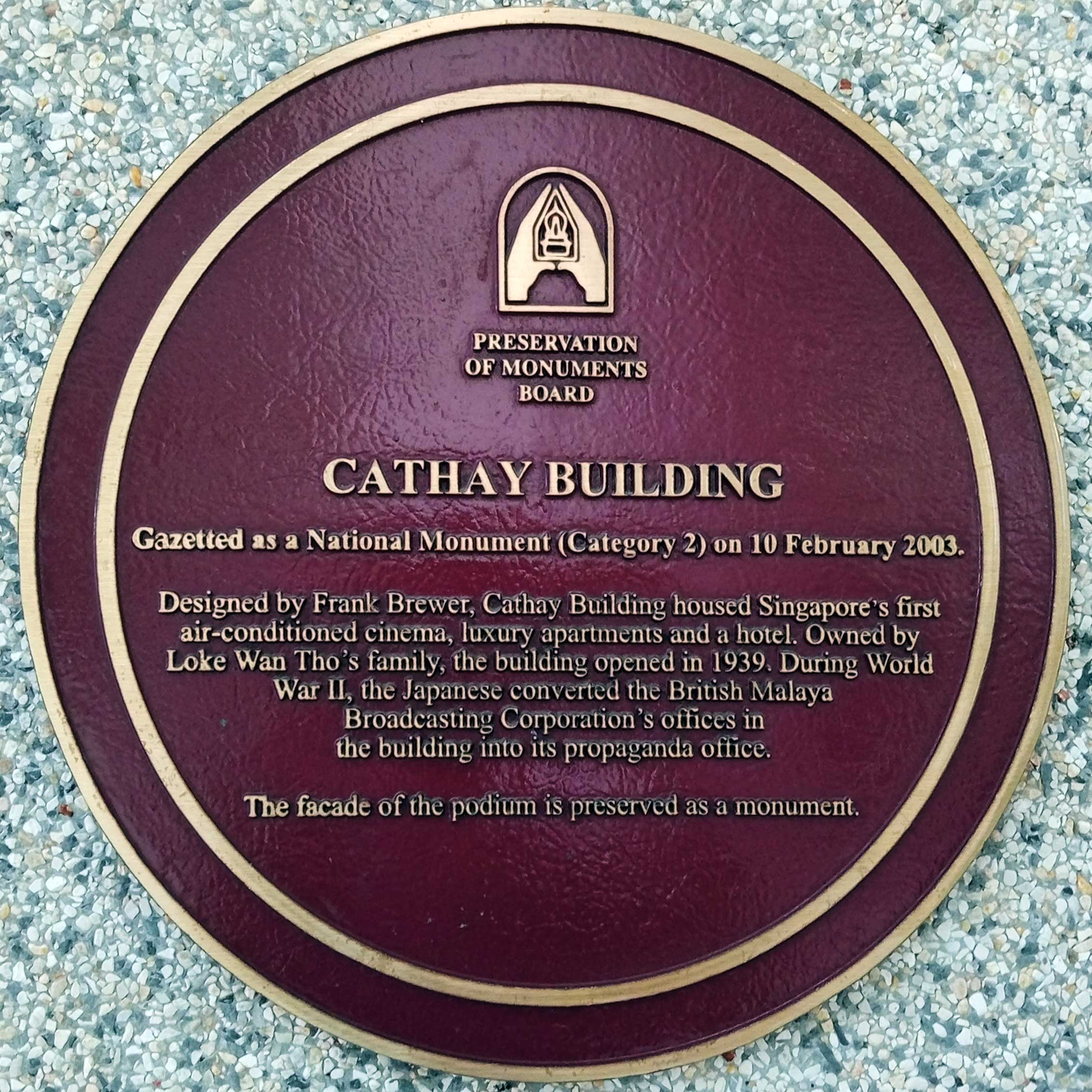

A National Monument

In 2000, Cathay Organisation had plans to redevelop Cathay Building for $100 million.14 Before the plan was approved by the Urban Redevelopment Authority, the then Preservation of Monuments Board identified Cathay Building as a possible landmark for preservation because of its history, especially during WWII.15 Cathay Building was gazetted as a national monument on 10 February 2003.

The cinemas in Cathay Building closed on 30 June 2000 for redevelopment. In line with its status as a national monument, the art deco facade of the building was preserved, with its geometric forms and curved, stepped walls. The name in vertical display was also retained. The rest of the building was redeveloped, and the original brown-tiled façade was incorporated into modern glass architecture.16

The Cathay reopened in 2006 with a shopping mall and an eight-hall multiplex – including Picturehouse, which had first opened in 1990 to feature art films.17

In 2017, Cathay Organisation sold its cinema business to entertainment company mm2 Asia for $230 million, and continued to own the Cathay Building and Cathay Cineleisure Orchard mall.18

Cathay Cineplex’s last day of operations was 26 June 2022, when it screened its final show, Top Gun: Maverick, at 9pm. The space used by the cineplex will be occupied by a pop-up run by The Projector from August 2022. Named Projector X:Picturehouse, the new cinema will show films and live performances.19

Soh Gek Han is the engagement editor of BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Kelvin Tong, “Akan Datang: Cathay’s New Home,” Straits Times, 4 April 2000, 4; “Cathay Building and YMCA Orchard Had a Grim Past,” Straits Times, 31 July 1995, 20; “I Built Highest, He Says,” Straits Times, 31 December 1953, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Cathay Cinema Opens Doors Tonight,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 October 1939, 5; “‘Four Feathers’ Released,” Straits Times, 30 July 1939, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Kay Tong, Cathay: 55 Years of Cinema (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1991), 98 (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 791.43095957 LIM); “Inside Singapore’s Newest Cinema Opens On Tuesday,” Straits Times, 1 October 1939, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Americans Celebrate Washington Day,” Straits Times, 22 February 1940, 10; “Jap Bombs Could Not Shake Its Spirit,” Malaya Tribune, 25 September 1949, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tommy Koh et al., Singapore: The Encyclopedia (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Heritage Board, 2006), 37. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57003 SIN) ↩

-

Koh, Singapore: The Encyclopedia, 37; Lim, Cathay, 100–102. ↩

-

“Syonan Broadcasting Station,” Syonan Shimbun, 28 June 1942, 3; “Syonan Broadcasting Station,” Syonan Shimbun, 26 July 1942, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim, Cathay, 104; “Govt. to Vacate Cathay Building,” Malaya Tribune, 28 January 1949, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Liquidate The Cathay Restaurant Opens May 1, Morning Tribune, 17 April 1948, 2; “Govt. to Vacate Cathay Building”; Lim, Cathay, 110. ↩

-

“Studios Turn into a Plush Hotel,” Singapore Standard, 9 January 1954, 2 (From NewspaperSG); Lim, Cathay, 110. ↩

-

“Tallest Skyscraper Opens,” Singapore Standard, 12 December 1955, 9; “Yes, You Can’t Miss the Cathay,” Singapore Free Press, 13 February 1959, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Vernon Cornelius-Takahama and Ong Eng Chuan, “Cathay Building,” Singapore Infopedia, last updated September 2020; Lim, Cathay, 110–11. ↩

-

“World War II Plaque (Outside Cathay Cinema),” Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, 1995–1999. (National Archives of Singapore media image no. 19990001374 – 0040) ↩

-

Chris Loh, “Cathay Building Is to Be Redeveloped for $100m,” Business Times, 19 February 2000, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leong Weng Kam, “Landmark Building May Yet Be Saved,” Straits Times, 6 April 2000, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Preservation of Monuments Order 2003, Sp.S 60/2003, Government Gazette. Subsidiary Legislation Supplement, 10 February 2003, 370 (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 348.5957 SGGSLS); “Cathay’s Contemporaries,” Business Times, 21 April 2000, EL1–EL2 (From Newslink via NLB eResources website); “Former Cathay Building (Now The Cathay)” Roots, last updated 5 May 2022. ↩

-

Ong Sor Fern, “The Cathay Reopens,” Straits Times, 25 March 2006, 2; Wong Kim Hoh, “When a Passionista Gets Dream Job, Sparks Fly,” Straits Times, 26 March 2006, 33. (From Newslink via NLB eResources website) ↩

-

Annabeth Low, “mm2 Asia Expands Footprint with S$230m Cathay Cinema Deal,” Business Times 3 November 2017, 8; John Lui, “Sudden Exits,” Straits Times, 23 December 2017, A10. (From Newslink via NLB eResources website) ↩

-

Shannon Ling, “The Cathay Cineplex in Handy Road, One of Singapore’s Oldest Cinemas, to Close after June 26,” Straits Times, 17 June 2022; Melissa Lin, “Cinema with a Grim and Glamorous Past,” Straits Times, 5 November 2017 (From Newslink via NLB eResources website); Ang Hwee Min, “A Subdued Final Day as The Cathay Cineplex Draws the Curtain on Operations,” Channel NewsAsia, 26 June 2022. ↩